3.1 Variables

A variable is a named location that stores a value inside a program. In Java, variables must have a name and a type. A type, or datatype, is the type of data a variable is allowed to hold. This could be a piece of text, a number, a picture, or nearly anything else. In the following sections, we will study what some of these types actually are in Java. But in this section we will use two common types - int and double. Sometimes a variable name is referred to as an identifier. But not all identifiers are variables; identifiers can also be method or class names. So we will call them variables unless referring to identifiers in general.

Neither the type nor the name of a variable can be changed once it is created. The only part that can vary is the value, hence variable.

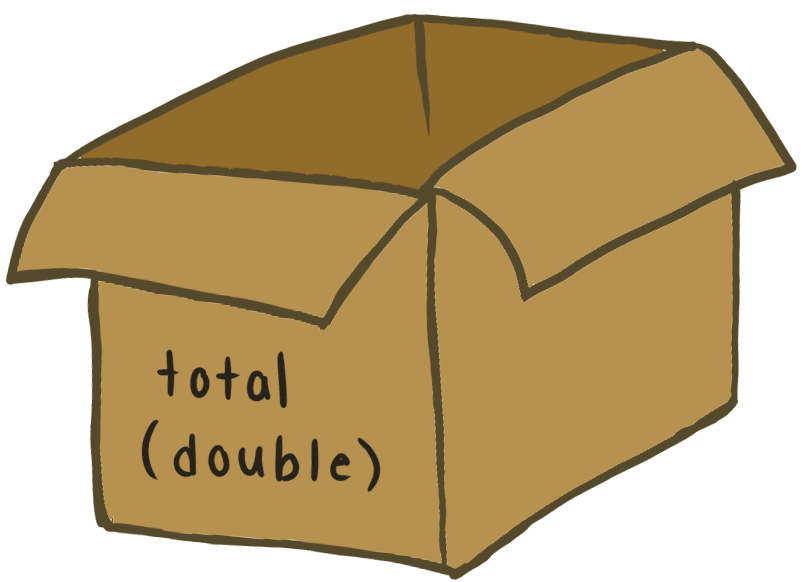

Throughout this chapter, we will use an analogy of a storaage box. On the outside, we must write the name and datatype on it with a permanent marker. Here, the datatype is in parentheses.

On the inside, we will have a piece of paper with a value. If we want to change the value of the variable (box), we replace the paper value with a new one, throwing away the original. When we assign a value to the variable (box), the piece of paper on the inside is the only thing that changes, the outside will always stay the same.

Declaration

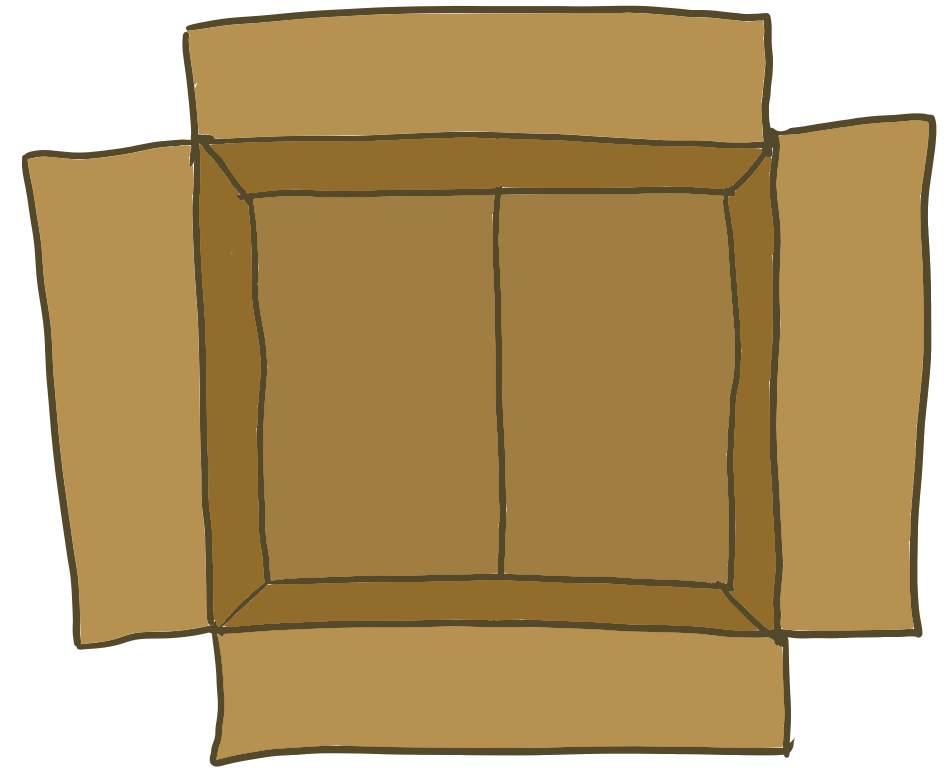

A variable declaration is a programming statement that declares a variable with a name and a type, but no value. This would be like grabbing a new box and writing the name and type on it. When just declaring a variable, there is no paper/value inside. This is called an uninitialized variable.

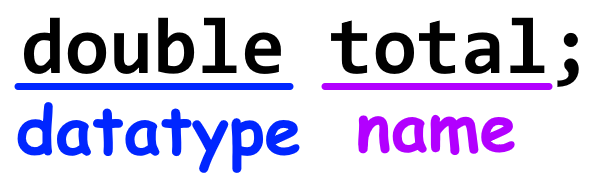

The general form of a declaration is DataType variableName;. For example,

When a variable is declared, it cannot be used until it is initialized. For this reason, it is uncommon to declare a variable without initializing it at the same time.

Initialization

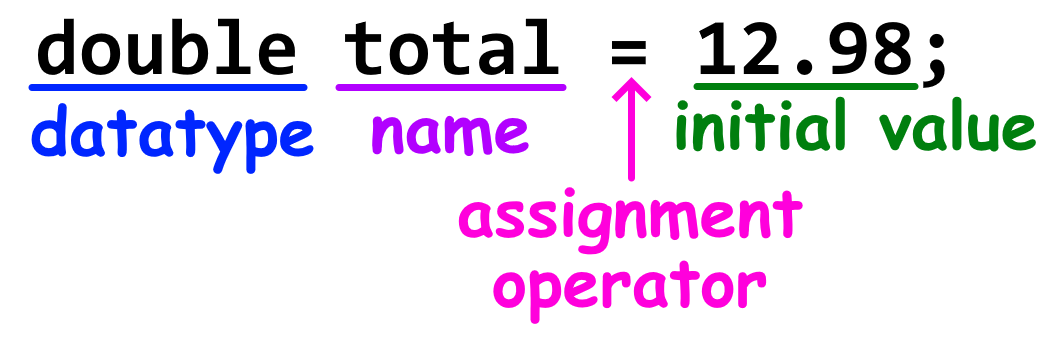

A variable initialization is a programming statement that initializes the value of a variable. The initial value must be the same datatype as the variable, or compatible with the type. We will see more on compatibility in the next section. In order to initialize a variable, we use the assignment operator, which is a single equal sign =.

double total; // Declare

total = 12.98; // Initialize

However, the above code is very rare. Instead, programmers usually declare and initialize a variable in the same statement:

// Declare and initialize

double total = 12.98;

The general form of a variable initialization is DataType variableName = initialValue;, and is better illustrated here:

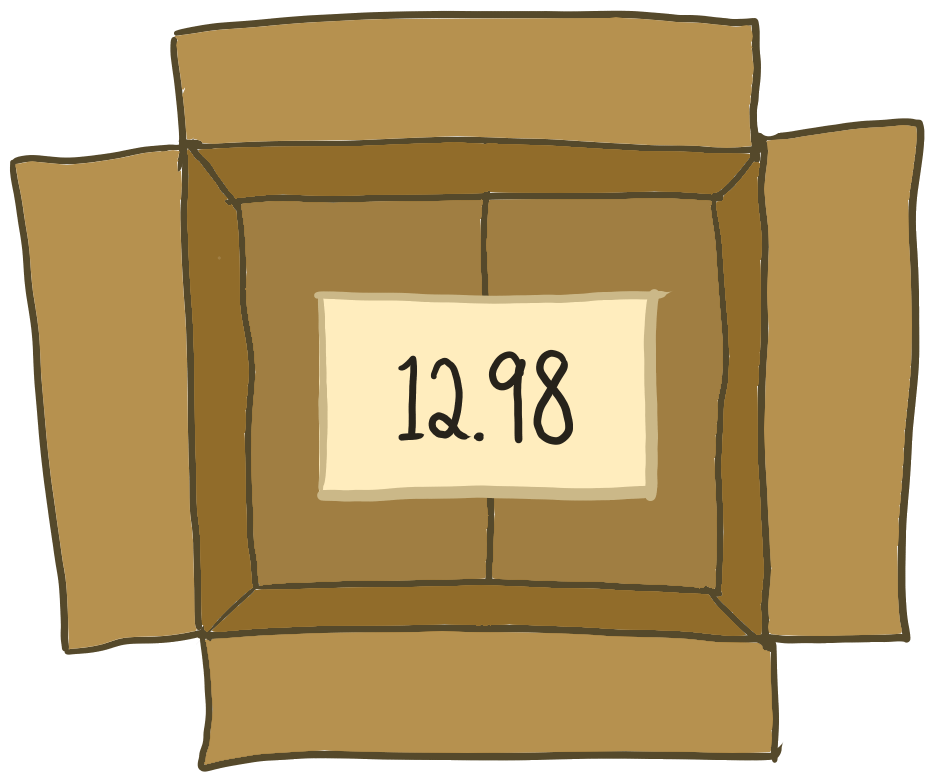

In our box analogy, this would be like putting this piece of paper inside the box labeled by total:

Variables can be initialized to more than just a constant. Often times, the value is the result of an expression. For example:

// Declare and initialize

double diameter = radius * 2;

Here, the diameter is initialized to twice the value of radius. So, if radius had a value of 5, then diameter would be the result of 5 * 2, which is 10. Whenever we use the variable diameter, it does not recompute radius * 2. Instead, the result of the expression is the value that gets stored. As such, if we later assigned radius = 7;, then diameter would still be 10.

double radius = 5;

double diameter = radius * 2;

System.out.println(radius); // 5

System.out.println(diameter); // 10

radius = 7; // Update radius

System.out.println(radius); // 7

System.out.println(diameter); // 10

Methods can be used as parts of initialization expressions, too, and we'll learn more about those in a @section3.3.

Static typing

Java is a statically-typed langauge, also called strongly typed. This means that all variables have a datatype and the value must be compatible with the type. This typing also determines what the allowed operations are for that type (operators are in @chapter4). Any type violations, such as storing text in a number, will cause a compilation error.

Using a variable

A variable is used anytime its value is accessed or copied. This is done by using the variable's name. Uninitialized variables cannot be used, and will cause a compilation error if you try. Note that a variable can be used multiple times, or not at all (which will likely show warning in your IDE).

In System.out.println(radius); we are using the radius variable. Almost every variable or expression can be printed with print and println. Variables can also be used in expressions, such as radius * 2. This expression reads the value from radius (by opening "the box"), and multiplies it by 2. We can print the result of this expression with System.out.println(radius * 2);.

Assignment

An important part about variables is that they can vary. A variable can be assigned to a value with a compatible type using the assignment operator =. The value can be a literal or an expression. Here are some examples:

// literal

int x = 5;

// result of an expression

int y = x;

// result of an expression

int z = x + 2;

Reassignment

Often times, you want to update the value of a variable after it has been initialized. This is called reassignment. The simplest form would be variableName = newValue;. Notice that the datatype is not declared again. Datatypes are only part of a variable declaration. When you reassign a variable, whatever data it previously stored is gone forever (unless you stored a copy in another variable beforehand). This is like replacing the paper in our box analogy.

An example of reassignment is below:

int x = 5;

System.out.println(x); // 5

x = 4;

System.out.println(x); // 4

Copying

When you assign a variable the value of another variable, it copies the value. In the box analogy, this would be like photocopying the paper in the original box, and placing the copy in the other box. After the value has been copied, anything that happens to either variable (box) is independent of the other. For example,

int x = 5;

int y = x; // store a copy of x, which is 5

x = 1 // updates x only

System.out.println(x); // 1

System.out.println(y); // 5

y was assigned a copy of x, which stored the value 5 at the time. These are two separate boxes, so when we say x = 1;, only x's box is updated. Therefore, when we print y, the original copy of 5 is still stored.

Chained assignments

Every so often, you will want to assign the same value to multiple variables. You can do this by chaining the assignment operator. Suppose you have a few variables holding counts of different things, and you want reset all of them to zero. Assuming all these variables are already declared (or initialized), you can write

appleCount = orangeCount = bananaCount = 0;

This will only evaluate the expression on the right side once. In this example, 0 is assigned to bananaCount, then bananaCount is copied into orangeCount, and finally orangeCount is copied into appleCount. This is not used very often, but can occasionally simplify a few lines of code. The longer way of doing the previous block of code would be:

appleCount = 0;

orangeCount = 0;

bananaCount = 0;

Multiple declarations and initializations

It is possible to declare multiple variables in a single statement. While I strongly discourage you from using this, I am still presenting it so that you can read any code that does it. This can be done with a comma-separated list of variables, all holding the same type. For example,

// Declare 3 double variables

double x, y, z;

// Declare and initialize 3 double variables

double x = 0, y = 1.5, z = 72.5;

// Declare and initialize some of the variables

double x, y = 1.5, z;

As you can see, once variable initializations are added, the readability diminishes. It is not that bad for simply declaring variables, but ultimately you will have to initialize them such as:

// Declare 3 double variables, then initialize

double x, y, z;

x = 0;

y = 1.5;

z = 72.5;

And at this point, you might as well have just done the normal way:

// Directly initialize 3 double variables

double x = 0;

double y = 1.5;

double z = 72.5;

Naming

The two hardest things in computer science are cache invalidation and naming things. This is a historical joke, but is accurate in a philosophical sense. For now, we will only look at one of them: naming things.

There are two main things to worry about: what we could name something, and what we should name something. The hard part is what you should name something, as the grammar of the language restricts what you could name it.

There are an infinite number of names you could choose, but which one would be the best? Would it be better to use numberOfUsers, userCount, or totalUsers? In this example, these are all good choices, but there will be other times when pinpointing a descriptive name is much trickier.

An important note is that variable names cannot be reused within the same scope. We will start to see scopes in @chapter6, but we have only used the scope of the main thus far. This means that all your variable names inside main must be unique. Fortunately, each method gets its own new scope, effectively resetting the used variable names, or else we'd have a really hard time naming things.

Allowed Names

An allowed name is what Java allows us to use - what we could use. Remember that Java is case-sensitive, so Total would be a different variable than total. Here are the naming rules:

- Cannot have whitespace.

- Must start with a letter,

$(dollar-sign), or_(underscore). - Subsequent characters can be letters, numbers,

$, and_. - Cannot be a reserved keyword.

- Can be context-sensitive keywords.

- Cannot be

true,false, ornull, as these are literals.

Reserved Keywords

Reserved keywords, commonly called keywords, are special tokens that cannot be used as an identifier. Some keywords that we have already seen are public, static, void, and class. A table listing all the reserved keywords is below. You do not need to memorize them. We will slowly learn about the different keywords when we cover their respective topics, 8 of which are in the next section. Besides, most of them wouldn't even be good variable names.

| abstract | continue | for | new | switch |

| assert | default | if | package | synchronized |

| boolean | do | goto | private | this |

| break | double | implements | protected | throw |

| byte | else | import | public | throws |

| case | enum | instanceof | return | transient |

| catch | extends | int | short | try |

| char | final | interface | static | void |

| class | finally | long | strictfp | volatile |

| const | float | native | super | while |

| _ (underscore) |

Contextual Keywords

Contextual keywords are keywords that are only reserved in certain situations. Most of these keywords were only added to newer versions of Java, so if they were fully reserved, old Java code using these keywords as variables wouldn't compile. So, contextual keywords were added to help with forwards-compatibility, meaning old code should still work on newer versions.

| exports | opens | requires | uses | yield |

| module | permits | sealed | var | |

| non-sealed | provides | to | when | |

| open | record | transitive | with |

Java Variable Naming Conventions

Now that we know what we could name a variable, lets discuss how you should (or shouldn't) name something. These rules are called naming conventions, and they help to keep Java source code consistent. That way, any Java developer could join any project and wouldn't have to learn a new set of rules, or would be able to read other developers code more easily. Most programming languages have well-established conventions, not just Java. The standard variable naming conventions in Java are as follows:

- Use lower camel-case.

- Do not use a

$in variable names. - Do not use

_in variable names (except constants). - Do not use any context-sensitive keywords as variable names.

In addition to the standard rules, there are also some common naming recommendations. Avoid using abbreviations and acronyms unless they are very well-known, such as HTML, GUI, or ID. This would also include avoiding no or num instead of number.

Camel Case

Lower camel-case, or simply camel-case, is a naming convention to combine multiple words into a single identifier (which cannot have spaces). It is defined by starting with a lowercase letter, and then the first letter of each subsequent word capitalized. In the end, the identifier somewhat resembles the humps on a camel's back. This is best described with some examples:

| Phrase | Lower camel-case |

|---|---|

| number of users | numberOfUsers |

| total price | totalPrice |

| count | count |

| subscription tier | subscriptionTier |

| average rainfall | averageRainfall |

| ID | id |

| favorite TV show | favoriteTvShow |