3.2 Primitive Data Types

Datatypes in Java are split into two categories: primitive and reference types. Primitive data types, or primitives, are the simplest types predefined by Java. Primitives are the closest thing to the raw binary values used by computer hardware. It is from these primitive types that all reference types can be built of. There are exactly 8 primitive types, but no limit reference types. The Java primitives are boolean, byte, short, int, long, float, double and char. Note, these constitute for 8 of the reserved keywords. The biggest differences are how many bits they represent and the allowed operations (such as addition and subtraction). Another difference is that primitives are better for performance.

Bits

A bit is a binary digit, which is either 0 or 1. A byte is a unit equal to exactly 8 bits. So, a 4-byte number would be 32-bits (8 × 4 = 32). A nibble is a unit representing half a byte (4-bits). The name nibble is a pun (half a byte/bite), and is fairly uncommonly.

A binary number is a number consisting of only binary digits, in base-2. Different bases, including binary, are covered in @appendix-B. A decimal number is a number in base-10, and is the most common numbering system. This is not to be confused with a decimal value, such as 1.5, which is a real number. A hexadecimal number is a number in base-16, where each digit can be one of 16 values (0-9 and A-F).

The binary number 100011 is 35 in decimal. How did 6 digits turn into 2? This is because a decimal number has more information per digit than a binary number. In base-10 each digit can be one of 10 possible values: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. But, in base-2 each digit (bit) can be one of 2 possible values: 0, 1. For every digit we can repeatedly multiply by the number of possible values (per digit) to get the total number of possible values for a number of that length. For some familiar examples in base-10, 2 digits gives us 10 × 10 = 100 values, 3 digits gives 10 × 10 × 10 = 1000 values, 4 digits gives 10 × 10 × 10 × 10 = 10000 values, and so on. Every digit we add gives us 10 times the number of possible values. When we consider these examples for binary (base-2), we instead have 2 digits gives us 2 × 2 = 4 values, 3 digits gives 2 × 2 × 2 = 8, 4 digits gives 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 = 16, and so on. Now each additional digit is giving us 2 times the possible values. We can better express this with exponents, so 4 digits gives us 24 = 16 values, 5 digits gives 25 = 32 values, and so on. This is why we need a lot more digits in base-2 to represent the same value in base-10.

Integers

An integer is an element of the infinite set {..., -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ...}. The ellipses (...) indicate the pattern repeats infinitely in that direction. An integer has no fractional component, so 1.5 is not an integer, but 1337 is. Sometimes people will refer to integers as whole numbers, but this is technically incorrect. A whole number is an element of the infinite set {0, 1, 2, 3, ...}. Whole numbers have zero, but don't have negative numbers. Further, a natural number is an element of the infinite set {1, 2, 3, ...}.

Java has 4 integer primitives. They are byte, short, int, and long. They are 8-bit, 16-bit, 32-bit, and 64-bit, respectively. These have very different ranges, as we will soon see. But, since these primitives are actually integers, we also need negative numbers. An unsigned integer is an integer type that does not have negative numbers. A signed integer is an integer type that has negative numbers. All of Java's integer primitives are signed.

When we consider an example using signed numbers, 3-bits still gives 8 values, we would have the range [-4, 3]. This is called interval notation, and [-4, 3] means all the numbers -4, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3. 4-bits would give 16 values with the range [-8, 7]. Now that we understand some examples, we can view Java's integer types in the table below.

| Type | Size | Range (Inclusive) | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

byte |

8-bit | [-27, 27 - 1] | -128 | 127 |

short |

16-bit | [-215, 215 - 1] | -32,768 | 32,767 |

int |

32-bit | [-231, 231 - 1] | -2,147,483,648 | 2,147,483,647 |

long |

64-bit | [-263, 263 - 1] | -9,223,372,036,854,775,808 | 9,223,372,036,854,775,807 |

Exactness

An important property of integer types is that they are exact. This may seem obvious, but when we talk about floating-point numbers, they are not exact. Since integers are exact, operations like addition and subtraction don't have any rounding errors or precision problems.

Choosing Which Type

Based on these ranges, you might be tempted to carefully pick a type that best matches each use-case. For example, choosing to use byte for someone's age (assuming nobody is older than 127). However, choosing like this is rarely the case. It can often lead to future problems (such as when someone turns 128), which can be difficult to change later on. On top of that, byte and short are difficult to work with because performing any operation almost always results in an int. For reasons like these, Java programmers very rarely use byte and short. But, they are sometimes used with arrays (a future topic) to process file or network data. For most things, we are left with choosing between int and long.

int is the most widely used integer type in Java. With approximately 2-billion positive values, it works for most things, but not all. You should ask yourself the question, "Could I possibly need more than 2 billion?" If your answer is yes or maybe, use a long. In a video game, currency might be an int, but what if someone plays a lot? For health bars, maybe an enemy boss will have more than 2 billion. While the chance is low, it's still realistic, so I would use long and never think about it again. Anything that is a small value, like the width and height of your monitor (in pixels), can be an int without issues.

A classic example of using int instead of long causing scaling issues was with IPv4. In the early days of developing the internet, we needed a way to uniquely identify each device that was connected: it's IP address. It seemed like a reasonable assumption at the time that having more than 4 billion (-2 to +2 billion) devices on the internet was unlikely. But several years later, the mistake was felt when we ran out of IPv4 addresses. 64-bit IPv6 was invented, but it was too late. There was no realistic way for everything related to the internet to switch to the new 64-bit standard. So NAT (network address translation) was invented as a workaround to the 32-bit address space.

In a large application, if you need uniquely identify someone or something, usually use a long (or something longer). "Better safe than sorry," as the old adage goes. This regularly applies to databases, where the row ID should usually be at least 64-bit.

When a long isn't enough

Maybe 9,223,372,036,854,775,807 is too small for your use case. If you still need a fixed length ID, a UUID represents a 128-bit integer. If you need an integer without a specific limit, then BigInteger is the Java class for you. The details of these types go beyond the scope of this chapter, but we will see them again.

Literals

A literal value is when you literally code in the value. An example usage would be int x = 125;, where 125 is an int literal.

Literal Types

When creating an integer literal, it is an int literal by default. There is no way to create a byte or short literal. You can have something that acts like a byte or short literal by assigning a value in the correct range to a variable of that type. Anything outside the range wouldn't compile. For example,

byte goodByte = 123; // In range [-128, 127]

short goodShort = 12345; // In range [-32768, 32767]

byte badByte = 200; // Error, not in range [128, 127]

short badShort = 54321; // Error, not in range [-32768, 32767]

An example of assigning a literal to each type is below.

byte a = 1;

short b = 2;

int c = 3;

long d = 4;

Long Literals

Notice that long d = 4; worked, even though it is actually an int literal. This is because of an implicit widening conversion. We will discuss conversions like this towards the end of this section. But if you tried to write long d = 2147483648; this would not compile since 2147483648 is outside the range of an int. In order to have a long literal you must add the letter L or l to the end of the number. But, because a lowercase l looks like a 1, it is conventional to use a capital L. For example,

long x = 2147483648L;

long y = 100000000000000L;

Adding Separators (Underscores)

When you read the literal number 100000000000000L, you likely could not tell what it was at first glance, or be able to easily count the zeros. The number is actually 100 trillion. Fortunately, we can add underscores ( _ ) between digits. This is usually done every 3 digits, like we do in the real world. Updating our previous examples, we now have:

long x = 2_147_483_648L;

long y = 100_000_000_000_000L;

Binary, Octal, and Hex Literals

Unless you purposefully change the base of the literal, it will be a base-10 (decimal) number. This is what you will want in the vast majority of cases. But in some instances it makes more sense to be written in another base. Supported literal bases cover the most widely used bases in computer science, namely base-2 (binary), base-8 (octal), and base-16 (hex). Each base has its own syntax, and follow similar rules. All the literals are still int by default, and in order to make a long literal, you still need to add the L. They are also constrained to the same ranges as base-10 literals and follow the same assignment and conversion rules.

Binary literals start with 0b (or 0B), followed by zeros and ones, such as 0b0001_0010. While the underscores are optional, it is good practice to separate binary literals every 4 digits (one nibble), or sometimes every 8 digits (one byte). Additionally, since underscores must go between digits, 0b_101 would be invalid since it is between a letter and a digit.

Hexadecimal literals start with 0x (or 0X), followed by any hex digit (0-9, a-f, A-F). There is no standard saying whether to use lowercase or uppercase hex-digits, so choose whichever. Just don't mix uppercase and lowercase hex in the same literal. For underscores, you don't really need them. If you do add them, space them every 2 or 4 digits. For example, 0xABCDEF or 0x8000_0000_0000_0000L. Like with binary literals, you cannot add an underscore immediately before or after the x.

Octal literals start with a 0 and are followed by at least one octal digit (0-7). That means 0 is a decimal literal, but 00 is an octal literal. This is the rarest literal to see, and it also doesn't have a good pattern to add underscores at. In fact, since there is no letter in the literal, you can add it after the starting 0, such as 0_1234. Unless you have a very particular usage for it, octal literals are not recommended, and IntelliJ will give you a warning if you use one. (Some languages actually define 0o as the octal prefix, which removes ambiguity, but Java does not have this.)

Examples

// Base-10

int decimal1 = 123;

long decimal2 = 123_456_789_123L;

// Base-2

int binary1 = 0b0100_0101;

long binary2 = 0b1111_1011_1101_1100_0001_1111_1001_1111_0000_1001L;;

// Base-16

int hex1 = 0xCAFE_BABE;;

long hex2 = 0x12_34_56_78_90_AB_CD_EFL;;

// Base-8

int octal1 = 0777;;

long octal2 = 0_0123_4567_0123_4567L;;

Overflow and Underflow

What happens when you exceed the range of an integer type? If you go above the maximum value, an integer overflow occurs. If you go below the minimum value, an integer underflow occurs. These do not cause any errors, but could cause bugs. This is caused by arithmetic operators like addition, subtraction, and multiplication. When a value overflows/underflows, it effectively "wraps around" to the other side. If you exceed the maximum, it continues counting from the minimum. If you go below the minimum, it starts counting down from the maximum. Some examples should better illustrate this.

| Input | Output |

|---|---|

| 2147483646 + 1 | 2147483647 |

| 2147483647 + 1 | -2147483648 |

| 2147483647 + 2 | -2147483647 |

| 2147483647 + 3 | -2147483646 |

| -2147483648 - 1 | 2147483647 |

| -2147483648 - 2 | 2147483646 |

| 1_000_000_000 + 2_000_000_000 | -1_294_967_296 |

This is not as big of an issue if you use longs instead of ints, as they have a much larger range, but it is still possible. Reference types like BigInteger don't need to worry about overflows, as there is no limit.

Floating-Point Numbers

A floating-point number is an approximate data type meant to represent real numbers, but are closer to rational numbers. A real number is an integer, rational number, or irrational number. A rational number, or fraction, is a number that can be written as a/b where a and b are integers. Rational numbers would include numbers such as 0, 25, 0.5, 0.12345, etc.

Unlike fractions, which can be decimal points or written as the ratio of 2 integers, floating-point numbers are only represented by a fixed number of decimal points (in a specific base). So if a number cannot be exactly represented within that many decimal points (such as a repeating decimal), it will be approximated. For example, if we had a base-10 floating-point number with 4 decimal places, 1/3 would have to be approximated as 0.3333 (since we only have 4 decimals). Therefore, when we multiply this by 3, we get 0.9999 instead of 1. This means that some floating-point numbers will be approximate, and some floating-point numbers will be exact. Because they could be approximated, never assume a floating-point number is exact.

Java has 2 floating-point primitives. These are float (32-bit) and double (64-bit). The name float is short for floating-point. The name double is short for double-precision floating-point, as it has approximately twice the decimal places as float. These are implemented using the IEEE 754 standard, which is detailed in @appendix-C. In summary, it stores a mantissa (fractional parts), an exponent, and a sign (positive/negative). The number is in base-2 (binary), so the fractions look like 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, etc. The exponent is a power of 2, to shift the decimal point around. It is like scientific notation. The table below summarizes float and double.

| Type | Size | Precision (Approx) | Smallest | Largest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

float |

32-bit | 7 digits | ±1.4 × 10-45 | ±3.4028235 × 1038 |

double |

64-bit | 15 digits | ±4.9 × 10-324 | ±1.7976931348623157 × 10308 |

The precisions listed above are actually approximations, since we are viewing these numbers in base-10. If we were looking at these in base-2 then their precision would be exact based on the mantissa's length.

Special Values

You may have noticed that the exponent ranges are different for positives and negatives. This is because there are certain reserved exponent-bit combinations. These are for the special values NaN, positive infinity (∞), and negative infinity (-∞).

NaN

NaN, which stands for not a number, is a special floating-point value that arises from an undefined operation or value. For example zero divided by zero (floating points), is NaN. The native square root of a negative number (which would be an imaginary number) is NaN. Other undefined operations like (∞ - ∞) can also produce NaN.

NaN is also special because it does not equal anything, not even itself. We will learn about the equality operator (==) in the next chapter.

Infinity

There is a positive infinity and a negative infinity represented by floating-point numbers. These can be produced by exceeding the maximum/minimum range for a floating-point's exponent, or the result of certain operations. This means there is no overflow/underflow that you would see wrap around with integer types. In the context of floating-point numbers, the term finite refers to a number that is neither infinite nor NaN.

Operations with infinity follow closely with how it would in mathematics:

- (𝑥 ÷ 0) is ∞ when 𝑥 is positive.

- (𝑥 ÷ 0) is -∞ when 𝑥 is negative.

- (∞ + 𝑥) is ∞ when 𝑥 is finite.

- (-∞ + 𝑥) is -∞ when 𝑥 is finite.

- (∞ - ∞) and (∞ + (-∞)) are

NaN. - ((-∞) + ∞) and (-∞ - (-∞)) are

NaN.

Other properties of infinity are that ∞ is greater than everything (except itself and NaN), and -∞ is less than everything (except itself and NaN).

Approximate

To emphasize, floating-point values are approximate. A classic example is the following:

// prints 0.30000000000000004

System.out.println(0.1 + 0.2);

This particular example acts like this because 0.1 and 0.2 are repeating decimals in binary (base-2). Finite precision and rounding cause most of these issues. It follows that you should never assume exactness when working with floating-point values (float or double). We will learn about operators in the next chapter, but both arithmetic and comparison operators are unreliable on floats. We can improve this by using a small error factor with absolute values, which we will see in the next chapter.

While they are approximate, the bit patterns are exact and deterministic. That is, 0.1 + 0.2 is always 0.30000000000000004. Equality checks will work, but they must be exactly the same. For example,

// prints true

System.out.println(0.1 + 0.2 == 0.30000000000000004);

// prints false

System.out.println(0.1 + 0.2 == 0.3);

Choosing Which Type

Almost always use double because of the increased precision and range. Sometimes, float is used for performance reasons and is still fairly accurate. But in these rare cases, you likely should not be using Java anyway.

You should not use either when you need something exact. The BigDecimal class, which we'll also learn about later, provides exact values with a near infinite precision, though it cannot store repeating decimals properly. It is also implemented in base-10 instead of base-2, so values like 0.1 and 0.2 can be stored exactly, without repeating decimals.

Literals

Floating-point literals are created directly in code. They can consist of a whole-number part, a decimal point, a fractional part, an exponent, and a type suffix. There are several combinations that are valid.

By default, the type is double. A type suffix can be specified to change this to a float, or explicitly make it a double. Using f or F will create a float literal. And using d or D with explicitly make a double literal. It is preferable to use the lowercase versions d and f. This applies to any of the following ways of writing floating-point literals.

Most commonly, a literal will start with digits, have a decimal point, and be followed by digits. For example, 2.0, 12.5f, and 123.456.

A number that looks like an integer literal (no decimal point) can be explicitly made a double literal by adding d, such as 100d. This also applies to numbers outside the range of int, such as 100000000000000000000000000d. A number can also end with simply a decimal point, such as 2., or 2.f.

A literal can start with a decimal point and be followed by digits, such as .5 or .5f.

While not a floating-point literal, you can assign an integer literal to a double or float, such as double d = 1;. We will understand this more when talking about type conversions.

Using Exponents

Literals can also be specified with an exponent, which is effectively scientific notation. The only difference is the scalar does not have to be in the range [1, 10). They consist of a normal literal, followed by e or E and an integer power (positive or negative). For positive powers, the + sign is optional. This creates the number raised to 10exponent, so 1.5e3 is 1.5 × 103. You can also specify digits (with no decimal) and then an exponent, such as 2e5 (2 × 105).

Hexadecimal Literals

Perhaps one of the most cursed things in Java is the ability to create hexadecimal floating-point literals. I highly recommend you to never use this, and you will never be quizzed on this. But, in the one in a million chance you ever read code with a hexadecimal floating-point literal, you'll know of its black magic.

You can write the floating-point number in base-16, and raise it to a power of 2. This can be done with 0x#.#p# where the #.# is a hexadecimal literal, and p# represents multiplication by 2#. So 0x3.4p5 has a base of 3 + 4/16, which is 3.125, then multiplies this 25, which is 3.125 * 32 = 104. The p can also be P, and can still end in a type suffix.

Adding Separators (Underscores)

Similar to integers, you can add underscores between digits to improve readability. A decimal point is not a digit, so it cannot be next to the decimal. An example would be 123_456.456_789.

Rounding

If you try to create a floating-point literal with too many digits for its precision, it will compile but be rounded. For example, if you enter 123456789.123456789_123456789d it will be rounded to 1.2345678912345679E8, which is equal to the literal 123456789.12345679d. Even if there are too many total digits, the power still remains intact. So 100000000000000000000000000002d rounds to 1.0E29.

Examples

float f1 = 2.5f;

double d1 = 43.21;

double d2 = 123.456d;

double d3 = 1_000_000_000_000_000_000.0;

double d4 = 1e50;

double d5 = 1.5e+50;

double d6 = 1.6e-50;

double d7 = 1.;

double d8 = .1;

Booleans

The simplest of all datatypes in the boolean. A boolean is either true or false. These two values are very powerful, while only representing a single bit of information. A value of true represents a bit in the on state - a value of 1. A value of false represents a bit in the off state - a value of 0. Java does not support writing booleans with 1 and 0, but they are commonly used when discussing booleans. Even though they represent 1-bit, the actual size used is not precisely defined.

The boolean type in Java uses the reserved keyword boolean. There are exactly 2 literal values: true and false. Here is an example of each literal:

boolean on = true;

boolean off = false;

Booleans are not very powerful on their own. They are most commonly used with conditional branching and looping, which are some of the most important topics in programming. These topics are covered in @chapter6 and @chapter7, so we'll use booleans a lot more soon.

Characters

A character is a single letter, digit, symbol, or control code. Characters are encoded as integers using a character set to map an integer to a character. A code point is the integer value of a character. ASCII is a standard character set, represented with 7-bits. ASCII characters are mostly those on a standard US keyboard layout. These cover the Latin alphabet in uppercase and lowercase. For example, the letter A has a code point of 65, and a lowercase a has a code point of 97. There are also 8-bit extensions of ASCII that maintain the same code points for the original ASCII characters, and add 128 new ones. While extensions like ISO/IEC 8859-1 can help with some common Latin script characters (e.g. é), it cannot cover all of them. So some standards were made with over a million code points, and a specific encoding schema. The most well known are UTF-8 and UTF-16. UTF-8 uses 8-bit multiples (8, 16, 24, and 32) for encoding, whereas UTF-16 uses 16-bit multiples (16 and 32). Both support the same unicode character set. This includes the basic multilingual plane (BMP) and all unicode characters. UTF-8 is the most widely adopted standard, and uses less memory to encode text consisting of mostly ASCII characters.

You can view a full list of 7-bit ASCII and an extended 8-bit ASCII charset here.

Java has a single character type named char. A char is a 16-bit UTF-16 encoded character. This means that 32-bit UTF-16 characters (surrogate pairs) cannot be encoded within a single char. When we learn about Strings in a couple sections, these surrogates can we used inside literals, but char literals only support 16-bit characters. Since a char has to map to a code point, and code points are unsigned, a char is actually an unsigned integer with an inclusive range of 0 to 65535.

Literals

A character literal is enclosed by matching single-quotes, such as 'A'. The character literal cannot be a 32-bit surrogate, but anything with a 16-bit codepoint is fine. While not a character literal, you can assign an int literal to a char, provided its in the range of [0, 65535], such as char c = 64000;

Escape Sequences

Escape sequences allow you to represent a literal character that would otherwise be invalid. Some of these for whitespaces were shown in the last chapter. Like a normal character literal, they need to be in single quotes, such as char c = '\n';.

\bbackspace\sspace\ttab\nnewline\fform feed\"double quote\'single quote\\backslash

For char, the \" double quote does not need to be escaped. It could be char doubleQuote = '"';. Also, an empty string is not allowed in a char - it must have a length of 1.

Hexadecimal Unicode Escapes

You can encode the character's code point directly using its hexadecimal value. This starts with \u and is followed by exactly 4 hex-digits. For example, '\u7D02', which would be the same as '紂'.

Examples

char a1 = 'a'; // code point 97

char a2 = 97; // code point 97

char b = 'b'; // code point 98

char space1 = '\s';

char space2 = ' ';

char newline = '\n';

char doubleQuote1 = '"';

char doubleQuote2 = '\"';

char singleQuote = '\'';

char backslash = '\\';

// cjk stands for "chinese, japanese, and korean"

char cjk1 = '\u811A'; // code point 33050

char cjk2 = '脚'; // code point 33050

Type Conversions

When working with primitive datatypes, you can convert between all primitives except boolean. Sometimes this happens automatically (implicit), and other times manually (explicit).

Casting

The way to explicitly convert primitive types is through casting. A type cast converts one type to another. The cast operator is the target type enclosed by parenthesis, such as (long). This operator must preceed the value to cast. For example, long x = (long) 12.5;.

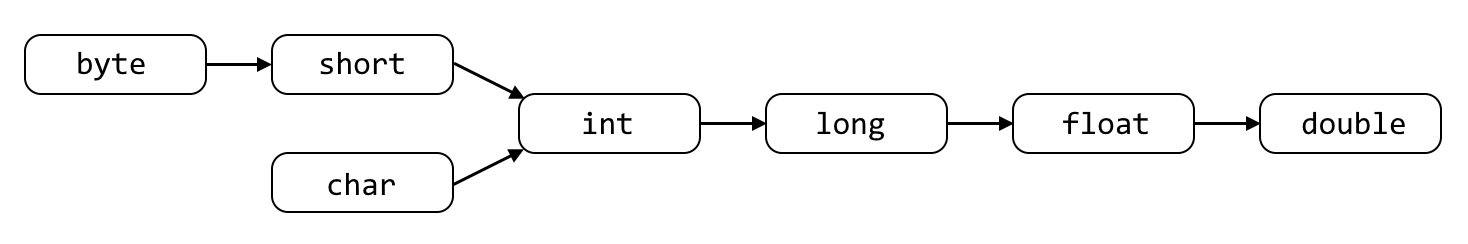

Depending on the original type and the target type, you might need to explicitly cast it. In general, if the target type can hold bigger numbers, it can be implicitly cast. The figure below shows the rules for implicit type casting. If there is an arrow connecting one type to another, it can be implicitly cast. Otherwise, it must be explicitly cast. For example, int can be implicitly cast to double, but cannot be implicitly cast to byte.

Implicit Conversions

An implicit type conversion is one that happens automatically, without the need for a type cast. This happens as an implicit widening conversion. The term widening means that the target type can store more data than the source. For example, if you took 100_000_000 as an int, you could directly assign this to long, since a long can hold anything an int can, plus more. You may still perform an explicit cast it to show intent, but you don't need to.

Explicit Conversions

An explicit type conversion is done manually with the cast operator. This is required for types going through a narrowing conversion. This means the target type is smaller than the source, so you may lose data. Consider casting a long value of 100 billion into an int, which can store approximately 2 billion. The resulting int will lose data, with truncation following the rules of integer overflow/underflow. Since you could lose data, this conversion must be done explicitly. Even if the long value is small enough for an int, you still need to explicitly cast it.

Floating-point to Integer

An important cast to understand is what happens to floating-point numbers when they are cast into an integer type. If the value is in the integer type's range, such as 5.3, then the result will be truncation after the decimal point. 5.3 will be truncated to 5, and 5.999 will also be truncated to 5. Everything gets rounded towards zero. If a value exceeds the integer's range, including infinity, it will cast as the minumum or maximum value for that type. So (byte) 1000.0 will become 127, and (byte) -1000.0 results in -128. For NaN, the result is 0.

Type Promotions

In general, operators on primitive types will result in the widest type of the operands, starting from int. This is why adding two byte values results in an int. If you add an int and long, the result is a long. A short and float will result in float. Adding an int and double will result in a double. Any type that is narrower than the result will be promoted to the resulting type before the operation is performed.

Summary

This was a very dense section to read, with tons of information to take in. I don't expect you to have remembered it all, but to at least have connected a few neurons. This is a section you can revisit later on, such as if you forget how to write a hexadecimal integer literal. However, there are some key takeaways you should absolutely remember:

- Integers are exact data types.

- Integers can overflow their values.

- Floating-points are approximate data types.

- Floating-points do not overflow, but have positive and negative infinity.

- Booleans are mostly used in conditionals and loops.

BigIntegerandBigDecimalcan be useful alternatives when primitives aren't enough.- Literal type suffixes are

dfor double,ffor float, andLfor long. - Underscores can improve number readability.

- Characters are UTF-16.

- Certain characters, such as backslash and single-quote, need to be escaped.

- Types can implicitly widen, but are explicitly narrowed.

- Casting a floating-point to an integer truncates the decimal point, rounding towards zero.